At the

Fifth Annual Conference for Funded Researchers, the center's director

Bill Maurer opened the proceedings both by speaking for the IMTFI and by offering his official greeting in his new role as Dean of the

School of Social Sciences for the entire UC Irvine campus. Maurer explained how the I

nstitute for Money, Technology, and Financial Inclusion approached the financial inclusion paradigm more capaciously by thinking about "not just money as cash" and how it had encouraged researchers to think about how money stores value -- as "value" is imagined very broadly, serves as a medium of many kinds of exchanges, and facilitates the transfer of wealth. In other words, money serves as an important actor in a multiplicity of relations between people and between people and objects. He noted that the Institute is also devoted to in-depth qualitative research that emphasizes "voices from the Global South" rather than parachute surveys that only confirm the findings that researchers cue subjects to produce. Furthermore Maurer asserted that the institute is committed to "building, nurturing, and sustaining a network people from different disciplines" and providing a scholarly and social space where anthropologists and economists can be in dialogue.

Speaking as a

scholar of digital media, who is interested in thinking about money as media,

as Marshal McLuhan did, I can attest to the warm welcome that the IMTFI provides to those of many disciplines and my own pleasure in serving as a guest blogger each year. Because of my own training as a rhetorician, I was drawn to the institute's work in uncovering narratives that sometimes contradict the official story about mobile money and bottom-of-the-pyramid economics. As Maurer observes, the "risqué" findings about the existence of gambling, fraud, and other behaviors in a more complex "moral gradient" than boosters may acknowledge can also include surprising findings, such as when monies supposedly designated for "school fees" that serve the development model paradigm are actually used for religious rituals, such as circumcision.

In "

Cashless or Cashlite? Mobile Money Use and Currency Redenomination in Zambia" by

Vivian Dzokoto and Mwiya Imasiku, the authors explore the interactions that resulted from two nearly simultaneous financial transformations that took place in the country: 1) the introduction of technology-based payment systems and 2) the reconfiguration of currency in its most basic form of cash. As Imasiku explained, the national bank changed the currency not only to increase citizen confidence but also to ease business transactions, which were to be made less complex by jettisoning three extraneous zeroes of place value. Thus Dzokoto observed that Zambia offered the opportunity to contrast the state of "cash-liteness" with the state of "cashlessness." When the Zambian Kwacha was changed as a unit of currency, researchers tried to look beyond big institutions to consider the impact on those considering the merits of cashlessness and cashlightness in the occupations of daily life and interviewed people such as fuel attendants who might be grappling with radical adjustments. They noted that a surprising 31% of those surveyed disliked the new currency and that approximately equal numbers thought businesses had and had not been affected by the currency change. Of particular interest to those thinking about money as an interface with material culture were the findings about how the public viewed the circulation of low denomination coins, which was much less positively than government policy makers had anticipated: with 16% of those surveyed expressing negative feelings about handling coins. In the researchers' study of whether or not passersby would pick up coins in public: 26% avoided picking up lowest denomination coins, and 8% would not pick up even the highest value of the coins. Ironically, people also thought coins were more useful to themselves than to others. Mobile money also faced challenges to implementation with 17% reporting "bad experience," and 12% of respondents describing lost phones. 61% used digital money for money transfers. Respondents did not think “safety” was an advantage; instead "speed" and "convenience" were seen as the advantages of mobile phone money. In general, the team reported "preferences for cash-lite not cash-less." In the question and answer session, mobile money was identified as a tool for saving by only 7% of those surveyed.

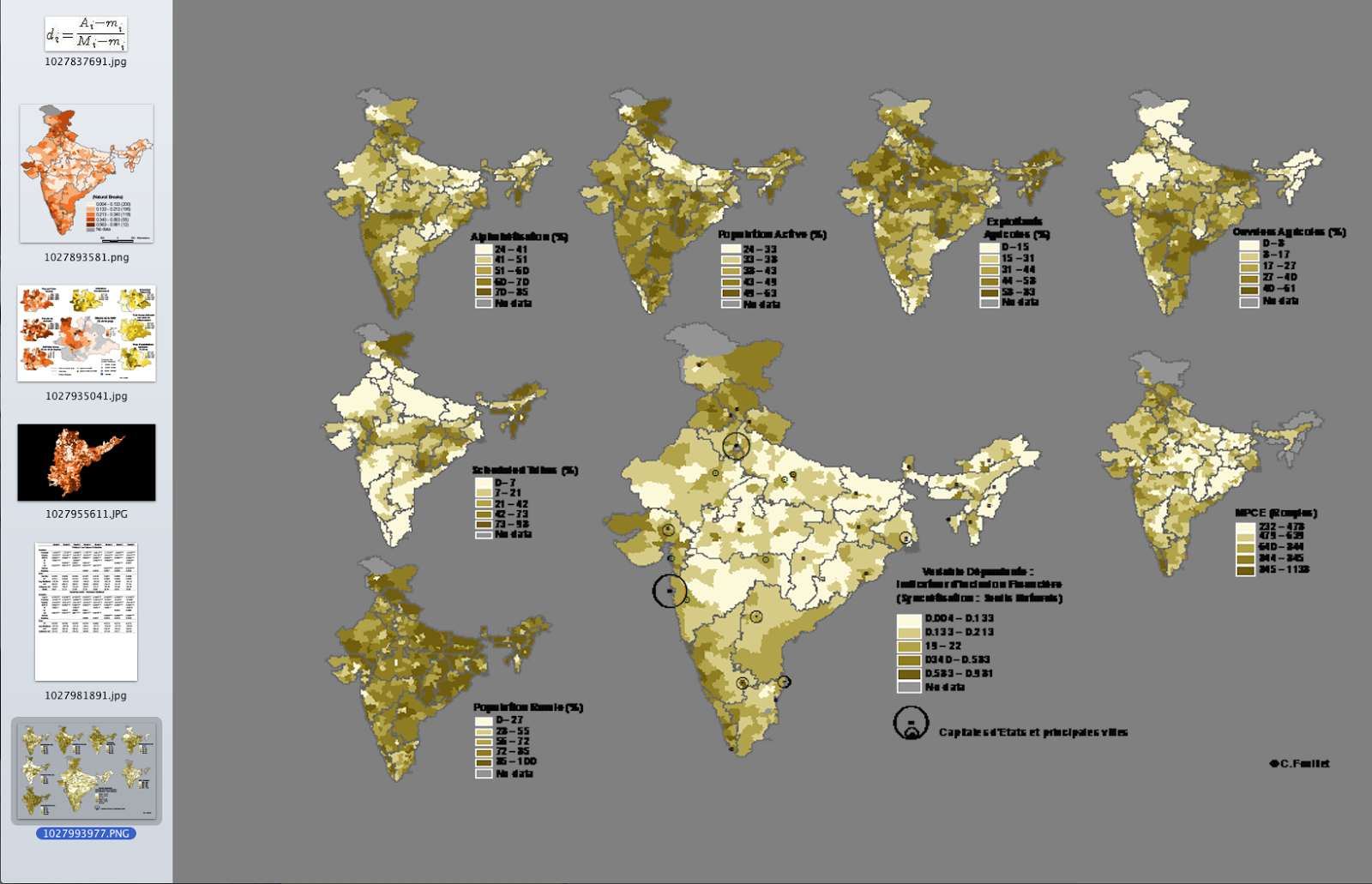

Amulya Krishna Champatiray and Parul Agarwal focused on kiosk banking in "

Exploring the Nature, Scope and Feasibility of Existing Technological Infrastructure of India's National e-Governance Plan's Customer Service Scheme Towards Converting In-cash Transactions into Cashless Transactions." They described how bureaucratic mechanisms drove the financial inclusion scenario in India, with the accessibility of government resources leading the way for social and private sector services. Champatiray and Agarwal characterized the nation's Internet access program as "massive" in its ambitions for 100,000 Internet-enabled kiosks across 600,000 villages in a network of hubs designed to increase accessibility and service delivery in keeping with the

National eGovernance plan. Such a model works on a PPP framework that emphasizes "purchasing power parity" rather than GDP as a way to understand people's attitudes toward branchless banking as part of the financial inclusion drive. Researchers emphasized considerations of financial viability and sustainability and identifying the motivations and aspirations of the VLEs who operate the kiosks that generate about 15,500 rupees for them as income.

Partnering with

AISECT, Champatiray and Agarwal surveyed 13 villages and quickly discovered that the majority of clients who came to the kiosks were school pupils. They also found that kiosks were generally opened by entrepreneurs seeking a second income stream and the social capital of enhanced reputation in the community. The kiosk client base is apparently grown when people share positive experiences, and billboards and signs primarily function to offer detailed information about costs and services to reduce information asymmetry. Such kiosks depend on a multi-service approach to generate revenue that includes providing one local venue to customers for bill paying, printing and photocopying, taking digital photographs, filling in forms, and verifying identification with statements needed for a bureaucratic society. Researchers asked farmers if they wanted price information from kiosks as well and found that those in agriculture would be mostly willing to use kiosks for cash transfers. Based on the generational divide that they observed, they found themselves with two further research questions: 1) does a school scholarship motivate parents to become banked and seek entry of the older generation into the formal financial sector, and 2) does the kiosk and scholarship routine inculcate a habit of saving and money management in future generations?

This Peruvian woman who runs a stationery stall might find it hard to look happy to encounter The University of Chicago's Eric Hirsch in what he called a "moment of hesitation or lingering." In his presentation, he explained how he tried to overcome the inherently unwelcome nature of his research on making change from large denomination currency by dividing the social and fiscally challenging interactions between fifteen separate people running small businesses, all but one of whom were female. In "

Investing in Indigeneity: Big Bills, Fungibility, and Mobile," he described his method of buying something small with a large bill to examine how big bills function as an obstacle to some transactions, because the currency was unwieldy, but as a facilitator of other kinds of transactions. Unlike the Zambian case study presented by the first panelists, Hirsch described a strong preference for coins that could provide exact change among the Peruvians he studied. Although there was unwillingness to accept the high value stored in bills, such currency was also associated with socially significant moments, which could configure how bearers of such bills manage complex networks of social relations.

Hirsch characterized Peru as a country in transition, as families turned away from living solely on their crops. Peru's 100 sol note operated as a specific kind of technological innovation, although all kinds of money had symbolic significance in the public sphere, as in the case of a bus driver clinging coins together to indicate the time to pay. Using the work of

Justin Richland, Hirsch discussed how Peruvians could "potentialize" cultural tourism to develop local cultural practices around microfinance and NGOs. He became interested in the problem of making change when studying how cooperatives handled dividing money equally and noted that the same term could mean both "to make change" and "to make sense." He observed that financial custodians would make an "activation purchase" at a local bodega, which kept large cash units provided by development dollars moving. In Peru's Colca Valley where state-led modernization programs promoted growth that followed "the financialization of development" model, he described locals "investing in indigeneity" as Western aid organizations such as the Peace Corps pulled out.

In exploring "what can cash units tell us about the relationships within a community," Hirsch aimed to "concretize meaning" and sort out the "pedagogical and moral messages" that could be decoded from the field site. By looking at the market in Chivay, and the fifteen market vendors who endured the change-making ritual, where Hirsch would routinely purchase an inexpensive item with big bill, he offered some preliminary conclusions about how bills move really fast or really slow, either like a "savings box" or like a "paper hot potato." He tried to engage the vendors in "substantive conversation," to record the interactions required to make change, and learn about the vendors personal and family expenses. For example, when buying from a snack stall, he observed the vendor "running to other vendors" to participate in other circuits of exchange and change. Similar work on the Sumac Yunque showed how association members managed household finances when running a home as site of indigenous identity, so it functioned as a museum and private archive. He saw order, reciprocity, and resentment of the "selfishness of people who don't make change" among his informants.

According to Hirsch, the presence of big bills was also taken "as a sign of the market's success" and a signifier of profit and investment. Although vendors rarely benefitted equally from such transactions, the longer term collateralized profit holding that big bills represented "convey meaning and organize relationships," because big bills were "highly conspicuous" (or what one participant in the audience from Ghana called the "flash factor" of the spectacle of cash. Hirsch argued that policy makers in Peru tended to focus on "inclusion for growth" not "growth for inclusion" as the motto for national strategy. By asking "what might be advantages of fungibility and alternative ways of living well," he hoped to get away from the fact that "development studies too often focus on a lack." Instead of emphasizing an "anthropology of poverty," Hirsch hoped to offer a more meaningful "study of wealth." During the question and answer session, one audience member pointed Hirsch to the research of

Jonathan Robinson on small market vendors in Kenya and the difficulties of making change in another national and social context.

Respondent

Scott Mainwaring, who has been a key participant at the IMTFI from the time of its founding, drew attention to the metaphors of light and heavy materiality that had been structuring the discussion and how "cashing out" might also function linguistically in complex ways.