The final panel of the conference was devoted to "Up(S)takes of New Financial Tools and Technologies" with discussant

Sonia Arenaza of the

Better Than Cash Alliance of the United Natons Capital Development Fund. Arenaza praised the from-the-ground perspective of panelists that provided "a human and social dimension" for developing digital financial services for underserved populations with the aim of creating a more "inclusive digital ecosystem" that considers social dynamics and ways to "broaden" connective chains.

In "

Separate self, interdependent self and new financial technologies - Lessons from rural southern India" Venkatasubramanian Govindan of the French Institute of Pondicherry described research in the field in Tamil Nadu as rural southern India undertakes a "massive effort to bank the unbanked citizen" with a focus on women and Dalits. The Prime Minister's ambitious

Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) initiative, which combines access to accounts with biometric authentication, attempts to launch new financial inclusion efforts on a massive scale. (For more on PMJDY, see

this IMTFI interview with Dan Radcliffe, which provides more information about this time of rapid change in India.) As Govindan explained, existing systems for smart cards and cash delivery -- combined with

NREGA (the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act of 2005) -- have created bureaucracies that aren't always easily accessible to villagers or comprehensible to their lifeworlds.

National banks may have obligations and relationships, but the role of villagers is "reduced to a minimum." Because they have had "no contact at all with the banks," which they perceive of as "distant," they "immediately withdraw payments." There also may be many logistical snafus in doling out resources. As the photograph above indicates, Govindan showed a video with villagers lining up for fingerprint authentication using a mobile machine in which a young woman is finally successful in completing the vetting process after frustrating glitches. (For more on the problems with authenticating identity in the new

e-Aadhaar system, see

this IMTFI blog post about the research of Mani Nandhi working with rickshaw pullers in Delhi.)

Govindan lamented the fact that with these ubiquitous computing devices there may be "problems with maintenance" and "few sites" capable of repairs. In the litany of other woes, he also mentioned insufficient cash, short battery charge life, inadequate transfers of the BC, and limited amounts on transactions. Furthermore, there may be caste conflicts governing who can hand cash to whom, which can be exacerbated when banks assume there are no distinction issues about accepting payment.

By exploring "the effects in terms of saving practices" and the "public dimension" of private financial practices, like other IMTFI researchers, Govindan emphasized the impact of "mistrust and rumors." He also highlighted the advantages of other saving practices, including ROSCAs (rotating savings and credit associations) and lending to others.In particular, he emphasized the fact that over 70% of saving was through acquisition of gold, (For more on gold economies among the poor, see this

in-depth profile of Nithya Joseph,)

He also shared a number of everyday practices of financial upkeep in an environment in which keeping bills is very uncommon by thinking about "the effects" of different financial inclusion efforts "in terms of worldview." He noted that financial calculations were often significant in planning for ceremonies, particularly ceremonies of marriage, puberty, and housewarming. A key life event might drain 4-8 years of household income, but such investments were critical in building respect (raiyatai). He noted how the "continuous chain of reciprocity" and local understandings of "accountability and debt payment" were important. He also stressed the importance of "mental accounting" among people with "little written culture" and how structures in which one person would be in charge of the family memory, including its financial memory, functioned. He closed be reiterating how the gap between financial inclusion objectives and people's practices had to be acknowledged, particularly "how people translate" when new initiatives are launched. A second round of household surveys is planned for the next phase of research.

"

Cross-border Transfers as a Strategic Tool to Promote the Diffusion of Mobile Money in Rural Areas. The Case of Burkinabe Diaspora Living in Ivory Coast" by

Solène Morvant-Roux of the Univesity of Geneva, Simon Barussaud of the University of Geneva, and Dieudonné Ilboudo of the National Centre of Scientific and Technological Research in Ouagadougou (CNRST/INERA) examined mobile money diffusion and its role in the economies of transnational migration.

The research team -- not all of whom could come to UCI -- began by providing an outline of their presentation, which followed the conventional social science template of "background," "methodology," and "findings" as its basic structure.

Morvant-Roux presented the existing empirical evidence on mobile money diffusion and usage on the domestic level before moving into their own case studies examining urban-rural transfers, where they were looking for international transfers between Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso. Researchers hypothesized that the introduction of mobile money in 2014 might be attractive to participants in the longstanding migration dynamic because of poor roads, spotty Internet services, and weak security, but they were wary of assuming patterns of usage that were solely instrumental. They planned their study by looking at the provision of mobile money services in comparison to other services, and they wanted to consider both the supply side and the migrant side of adoption potential. They also considered age, gender, location, and mobility as explanatory factors, as well as an analysis of the broader socio-economic and socio-political context. For migrants, "maintaining ties to one's own country" might be complicated, and the "emergence of new brokerage dynamics" might take surprising turns.

Barussaud explained how they conducted the survey first in Ivory Coast and then in Burkina Faso during January and February. He described how they undertook to survey a "broader view" of mobile money diffusion by deploying a mixed methods approach, which included 250 interviews, 337 transfers, focus groups, and analysis of secondary data. They chose the first field site based on immigration data. It was a site dominated by coffee plantations, where foreigners in area accounted for 45% of the population. The second area was chosen based on the first, as the origin point of significant chain migration. By identifying two major hubs, they hoped to better understand family configuration (which was transnational and often polygamous and constituted with an average of 12 members) and economic activities related to the 80% of migrants laboring on cocoa and coffee plantations, although there had been attempts at diversification with farming rubber trees and palm nuts. The picture of financial practices showed low formal inclusion at a level of less than 20% of participants and the characteristics of income seasonality.

Researchers focused on recent and regular transfers, at a typical rate of 5-7 per year, as part of the rhythm of migration pattens that were now over 20 years in the making with a number of second-generation migrants in the mix. Data collection tools included discussions with migrant workers and spouses and family members (155 family members in Ivory Coast and 100 in Burkina Faso), as well as geographical methods including geopositioning and light surveys. They also looked at census data and the typology of remittance service providers, to understand the supply-side dynamics.

International companies (like Western Union and MoneyGram) had been providers since the early 2000s, but these companies relied on Internet technology and consequently had a very reduced network. West African companies (like Wari, and Quick Cash) were able to take advantage of GSM technology and had been subregional economic players since 2010. The third set of actors on the supply-side had been the newer M-wallet services. Because mobile money induces a spatial diffusion of financial and transfer services, researchers wanted to look at the difference between 2012 and 2015 in mobile money diffusion. Uptake was often frustrated by a number of factors, including the difficulties of cashing out, spatial disparities, interoperability challenges that could lead to network disturbances, and the exclusion of women. In addition to gender gaps and generational gaps, there were also issues of illiteracy and mastery of technology, as well as trust gaps and innovation reluctance.

The sessions with the in-process researchers ended on a playful note with "

Exploring Rosca Dynamics with a Cambodian Factory Worker Board Game" by Andrew Crawford of Monash University who had been working with IMTFI to create a game about Rotating Savings and Credit Associations. Crawford has a history of thinking about entertainment and affect in financial inclusion efforts. For example, you can read about his work on promoting financial literacy through television comedy, particularly on buses,

here.

Crawford began by thanking those at the IMTFI conference who had during lunch played the T

ong Tin Game. (See below for a photograph of play testing at the IMTFI conference.) He noted the distinction between more static ROSCAs and bidding ROSCAs, that already incorporated some elements of gamification. (For more explanation of how gamification works, see this

online course from U Penn professor Kevin Werbach.) In a bidding ROSCA each member contributes a monthly deposit and a lump sum can be paid out to one member who needs access to credit and who bids the highest interest rate. From this structure can emerge poker-like dynamics of anticipating risks and bluffing. The idea for

Tong Tin grew out of an original IMTFI workshop in 2014. Crawford showed video of IMTFI researchers listing their different needs that were translated onto cards, including money to travel to a wedding on other side of Cambodia, a husband who lost his job, a daughter who was pregnant, an opportunity to buy land, a husband was jailed, an a husband's medical expenses. (The concept of playtesting is central to the game design process for both commercial and so-called "serious games" created by nonprofit organizations and independent developers. See this

list of best practices for playtesting to see how Crawford has integrated these principles.

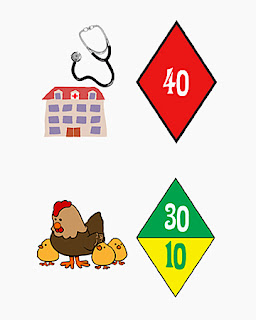

The rules of the game represent how people are incentivized to participate by the potential to make a high return, To reflect the economic environment of the garment factory the board is shaped like a button. On the 28-day circle representing the workers' factory month there is a square with a payday, a square with the ROSCA meeting, and other types of squares corresponding to green, red, and blue cards. The player begins the game with 100 dollars. In addition to payment on the payday, players may also have opportunities to buy assets like a chicken or experience setbacks like a dental crisis. Blue squares can move you either backward or forward.

Approximately 70% of Cambodian factory workers are involved in Tong Tin groups, which offer additional opportunities to earn capital. Among factory workers, both cashing out and stealing occurs, but there is still a strong trust element. In the game you can help people and experience the dynamics around borrowing (including consideration of interest rates, indebtedness, and emergency funds) and strategize about savings and investment (considering factors like a high rate of return, storage of savings, and the ability to cash out). The game also models trust and loyalty in rates and flight risks and asset purchasing with borrowed funds. It is designed to educate young people about ROSCA risks and benefits.

In addition to its didactic purposes as "a good way to understand the system," using a game also has many benefits to research. According to Crawford, "people don't want to talk about personal finance," but the "game format allows you to collect data" more naturally. He also showed video of playtesting with Cambodian workers, as the frame above taken from his footage shows. He organized 5 sessions of playtesting with his prototype, using 30 minutes of play with 8 players, 30 minutes of focus groups, and 30 minutes of one-on-one tablet surveys. Because factory workers had little time to spare, short sessions were critical for gathering data. He noticed some interesting quirks in the field site, including people's reluctance to draw cards from the top. He observed that a reliable chief player was critical to the game, as a figure for providing insurance as well as keeping hold of money.

Crawford still plans some revisions based on his findings. In working with the prototype he realized that he had underestimated the cost of a pig stock. He also noticed problems with using clip-art illustration with stock images. As one informant noted of a conventional portrayal of a thief: "the white guy stole your money." He has been partnering with

Winrock International, which is already in the region working on human trafficking and shares his enthusiasm for helping people learn "how to grow their assets instead of going to Thailand." He has concluded that more research from behavioral studies in anthropology and behavioral economics will be helpful and is planning use in schools in both developing and developed countries, so that more affluent young citizens might gain empathy for the challenges of managing money in developing country, and hopes to develop mobile apps with the game as well. For those interested in the possible etymological origins of his "Game to Reap and Sew," check out the eighteenth century investment scheme

Tontine.

The lively question and answer session emphasized the problem of "the one percent" in developing countries as asymmetrical stakeholders in inclusion efforts and critical reflection on the ethics of participation for researchers in countries in which wealth distribution is so uneven.